Notes on Linear Algebra¶

These are some notes on Linear Algebra which I prepared for a group of students I was teaching. They are in no way complete but they aim to clarify some common misconceptions and provide a solid basis for further study.

Matrix vector multiplication¶

I find it confusing to think about vectors and matrices as seas of numbers. Instead I find it simpler, and more geometrically intuitive, to see them as stacked sets of row or column vectors. This is the approach I’ll use in these notes and is also one I suggest you attempt to master. It can often reduce a linear algebra proof to a few lines.

Left-multiplication¶

A \(1 \times N\) vector, \(\vec{x}\), multiplied by a \(N \times M\) matrix, \(A\), gives a \(1 \times M\) vector which is the dot product of \(\vec{x}\) with the columns of \(A\).

Right-multiplication¶

A \(N \times M\) matrix, \(A\), multiplied by a \(M \times 1\) vector, \(\vec{x}\), gives a \(N \times 1\) vector which is the dot product of \(\vec{x}\) with the rows of \(A\).

The four fundamental subspaces¶

The row space¶

The row space of a \(N \times M\) matrix, \(A\), is the \(M\)-component space spanned by the rows of \(A\). If \(\vec{x}\) is in the row space of \(A\) then at least one of \(\vec{x} \cdot \vec{a}_i\), where \(\vec{a}_i\) is a row of \(A\), must be non-zero by definition. The dimension of the row space is equal to the rank of the matrix.

The null space¶

The null space of a \(N \times M\) matrix, \(A\), is the \(M\)-component space of vectors, \(\vec{x}\), for which \(A\vec{x} = \vec{0}\). Looking at our definition of the row space, it is clear that if a vector is in the row space it cannot be in the null space and vice versa. Therefore the row space is the compliment of the row space.

The column space¶

The column space of a \(N \times M\) matrix, \(A\), is the \(N\)-component space spanned by the columns of \(A\). If \(\vec{x}\) is in the column space of \(A\) then at least one of \(\vec{x} \cdot \vec{a}_i\), where \(\vec{a}_i\) is a column of \(A\), must be non-zero by definition. The dimension of the column space is equal to the rank of the matrix.

The left null space¶

The left null space of a \(N \times M\) matrix, \(A\), is the \(N\)-component space of vectors, \(\vec{x}\), for which \(\vec{x}^TA = \vec{0}^T\). Looking at our definition of the column space, it is clear that if a vector is in the column space it cannot be in the left null space and vice versa. Therefore the column space is the compliment of the left null space.

The rank of a matrix¶

The rank of a matrix is an important concept. As we have seen, if a matrix is not full-rank then the left-null space and null space must be non-zero and so some information from a vector will always be ‘thrown away’ (or set to zero) by the matrix.

Matrix-matrix multiplication¶

Like matrix-vector multiplication, it is best to think of this as a set of row-wise and column-wise operations.

Orthonormal matrices¶

An orthonormal matrix is one where all columns are independent and have unit length. If \(\{ \vec{a}_i : i \in 1 \dots M \}\) are the columns of an orthonormal matrix then it follows from the definition that

By using this result and looking at our representation of matrix-matrix multiplication above it should be clear that, if \(Q\) is an orthonormal matrix, \(Q^TQ = I\) and hence the transpose of an orthonormal matrix is its inverse.

The rows of \(Q\)¶

Further, if \(Q^T\) is the inverse of \(Q\), then \(QQ^T = I\) and hence \(Q^T\) must itself be orthonormal. Since, by definition of an orthonormal matrix, the columns of \(Q^T\) are independent and have unit length then it follows that the rows of an orthonormal matrix are also independent and unit length.

The geometric interpretation of orthonormal matrices¶

The geometric interpretation of the action of an orthonormal matrix can easily be seen by considering the actions of an \(N \times M\) orthonormal matrix \(Q\) with rows \(\{ \vec{q}_i : i \in 1 \dots N \}\) on a \(M \times 1\) vector \(\vec{x}\). Each component of \(Q\vec{x}\) is \(\vec{x}\) resolved onto one of the rows of \(Q\). Since the rows of \(Q\) are independent and have unit length, this results in a change of co-ordinates for \(\vec{x}\), resolving it onto the basis formed by the rows of \(Q\). In summary, an \(N \times M\) orthonormal matrix resolved a \(M\)-component vector into a \(N\)-dimensional subspace and a square orthonormal matrix transforms from one co-ordinate system to another without a loss of information. This last statement also justifies our implicit assertion above that all square orthonormal matrices are invertible.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors¶

An eigenvector, \(\vec{v}\), of some square matrix, \(A\), is defined to be any vector for which \(A \vec{v} = \lambda \vec{v}\). By convention we choose that eigenvectors have unit length although we are in general free to choose the length of eigenvectors. The value \(\lambda\) is an eigenvalue of the matrix, \(A\). We do not consider the vector \(\vec{0}\) to be an eigenvector of a matrix since it trivially satisfies the requirements for all square matrices.

A left-eigenvector of some square matrix, \(A\), is a vector, \(\vec{v}\), which satisfies \(\vec{v}^T A = \lambda \vec{v}^T\). It is obvious that the eigenvectors of a matrix are the left-eigenvectors of its transpose.

Eigenvectors of symmetric matrices¶

In general eigenvectors need not be orthogonal to each other but there is a special case where they are. Suppose the square matrix, \(A\), is symmetric so that \(A^T = A\). In this case the left-eigenvectors and left-eigenvalues are the same as the eigenvectors and eigenvalues.

Suppose two eigenvectors, \(\vec{e}_1\) and \(\vec{e}_2\) with associated eigenvalues \(\lambda_1\) and \(\lambda_2\), were non-orthogonal. In which case, we could represent one as some offset from the other: \(\vec{e}_2 = \alpha \vec{e}_1 + \vec{\Delta}\) where \(\vec{e}_1 \cdot \vec{\Delta} = 0\). Now consider multiplying \(A\) on the right by \(\vec{e}_2\):

By this result and the orthogonality of \(\vec{e}_1\) and \(\vec{\Delta}\) it follows that \(A\vec{\Delta} = \lambda_2 \vec{\Delta}\). Hence, by definition, \(\vec{e}_2 = \vec{\Delta}\) and is orthogonal to \(\vec{e}_1\).

This is a sketch proof and is non-rigorous but provides a justification for the claim that the eigenvectors of a symmetric matrix are orthogonal. A rigorous proof adds the condition that the matrix be of a form known as positive semi-definite but this is beyond the scope of the course.

Relation to the fundamental subspaces of a matrix¶

Looking at the definition of right-multiplication above it should be clear that if a non-zero vector \(\vec{b}\) can be expressed via another vector \(\vec{x}\) applied to \(A\) so that \(A\vec{x} = \vec{b}\) then \(\vec{x}\) is in the row space of the matrix. In other words, \(\vec{x}\) is non-orthogonal to at least one row of \(A\) since \(\vec{b}\) has at least one non-zero component.a By a similar argument, if \(\vec{x}^T A = \vec{b}^T\) and \(\vec{b}\) is non-zero, then \(\vec{x}\) must be in the column space of \(A\).

It follows that all eigenvectors of a square matrix must be in the row space and all left-eigenvectors of a square matrix must be in the column space. Since, for a symmetric matrix, the left-eigenvectors are the same as the eigenvectors, for a symmetric matrix, the eigenvectors must lie in both the column space and the row space.

As the eigenvectors for a symmetric matrix must be orthogonal and are by convention unit length, it may be no surprise to you that the eigenvectors of a symmetric matrix form an orthonormal basis for the row and column spaces. It is instructive to attempt to show this. It may be done quite simply using a similar method to that used to show the orthogonality of a symmetric matrix’s eigenvectors above: consider some vector composed of multiples of the eigenvectors and a remainder term orthogonal to all eigenvectors and then right-multiply the matrix by it.

Since the eigenvectors of a symmetric basis span the column and row spaces and since they are orthonormal, it should be cleat that the number of eigenvectors for a symmetric matrix equals its rank.

The eigenvector decomposition¶

Consider some \(N \times M\) matrix, \(A\). We can form two symmetric matrices from it: the \(N \times N\) matrix \(AA^T\) and the \(M \times M\) matrix \(A^TA\). If \(V\) is a matrix whose columns are eigenvectors of \(A^TA\) and \(U\) is a matrix whose columns are eigenvectors of \(AA^T\) then, by definition,

where \(\Lambda_V\) and \(\Lambda_U\) are matrices whose diagonal elements containing the appropriate eigenvalues. The size of \(\Lambda_U\) and \(\Lambda_V\) depend on the ranks of \(AA^T\) and \(A^TA\) respectively. If you look up the properties of ranks, you’ll discover that the ranks of \(A^TA\) and \(AA^T\) are equal to the rank of \(A\). Let’s call it \(R\). In this case, therefore, the matrices \(\Lambda_U\) and \(\Lambda_V\) are \(R \times R\), where \(R = \mbox{rank}(A)\).

Since we know that \(V\) and \(U\) are orthonormal, their inverses must be their own transpose and so we can rearrange the above as follows:

This is called the eigenvector decomposition of \(A\).

Eigenvalues of \(AA^T\) and \(A^TA\)¶

Imagine, for the moment, that \(\vec{v}\) is an eigenvector of \(A^TA\) with associated eigenvalue \(\lambda_v\). Then, by the definition,

Hence if \(\vec{v}\) is an eigenvector or \(A^TA\), then \(A\vec{v}\) is an eigenvector of \(AA^T\) with the same eigenvalue. Similarly, if \(\vec{u}\) is an eigenvector of \(AA^T\) then \(A^T\vec{u}\) is an eigenvector of \(A^TA\) with the same eigenvalue. In summary, the eigenvalues of \(A^TA\) and \(AA^T\) are identical.

Because of this, we can always choose the ordering of \(U\) and \(V\) so as to make the diagonal terms of \(\Lambda_U\) and \(\Lambda_V\) identical and hence make both matrices equal to some diagonal matrix \(\Lambda\). The way this is done is that, conventionally, the columns of \(U\) and \(V\) are ordered by decreasing eigenvalue.

In summary, when the columns of \(U\) and \(V\) are arranged in decreasing order of eigenvalue, we may form two related eigenvector decompositions of \(A\):

Since each eigenvector of \(AA^T\) maps to an eigenvector of \(A^TA\) and vice-versa, we can be confident that the ranks of \(AA^T\) and \(A^TA\) are identical. This is yet more justification of the assertion about the sizes of \(\Lambda_U\) and \(\Lambda_V\) above.

The singular value decomposition¶

For the moment, suppose that there is some decomposition of an \(N \times M\) matrix \(A\) into a \(N \times R\) orthogonal matrix \(U\), a \(M \times R\) matrix \(V\) and some \(R \times R\) matrix \(\Sigma\) whose only non-zero terms are on the diagonal:

Consider the form of the matrices \(A^TA\) and \(AA^T\):

If we make the observation that we may set \(\Sigma^T \Sigma = \Lambda_V\) and \(\Sigma \Sigma^T = \Lambda_U\) then we have exactly the eigenvector decomposition. Further, since \(\Lambda_U = \Lambda_V = \Lambda\), then we can see that \(\Sigma\) is the \(R \times R\) diagonal matrix of eigenvalue square-roots.

The decomposition \(A = U \Sigma V^T\) is called the singular value decomposition (SVD). The columns of the matrices \(U\) and \(V\) are the eigenvectors of \(AA^T\) and \(A^TA\) respectively ordered by decreasing eigenvalue. The non-zero elements of \(\Sigma\) are called the singular values and the number of singular values is equal to the rank of \(A\).

The geometric interpretation of the SVD¶

We can interpret the SVD of a \(N \times M\) matrix geometrically. The action of the first orthonormal matrix \(V^T\) is to transform a \(M\)-component vector into a \(R\)-dimensional subspace. This will lose information if \(R < M\). In this subspace, the action of the matrix \(A\) is to scale along each of the basis vectors by the values of the diagonal of \(\Sigma\). Finally, the orthonormal matrix \(U\) transforms from the \(R\)-dimensional subspace into the \(U\)-component space we expect the result to be in. This transform cannot invent new information; the result of applying \(U\) is still \(R\)-dimensional, it is just a \(R\)-dimensional subspace embedded in a \(N\)-dimensional space.

It is this ‘necking’ into a \(R\)-dimensional space that shows up if the matrix \(A\) is invertible in and of itself. If \(R < M\) information will be lost and so the matrix could never be invertible.

Matrix approximation¶

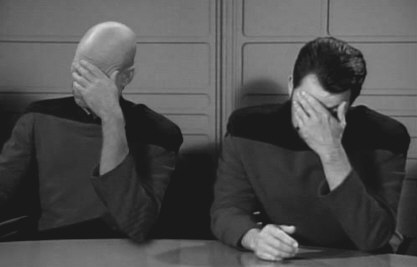

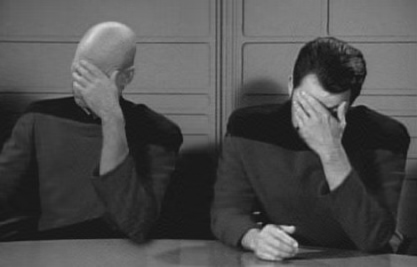

The SVD may be used to approximate a matrix. Instead of retaining the full \(R\) diagonal entries of \(\Sigma\), we may truncate the matrix and keep only the first \(R' < R\) entries of \(\Sigma\) and the first \(R'\) columns of \(U\) and \(V\). The following figures give an example of this so-called rank reduction applied to a matrix representing an image. Under each image is shown the number of singular values (s.v.s) retained and the corresponding amount of storage required for the image as a fraction of the original. The SVD can be used as a naïve form of image compression; we managed to get to around 16% of the original image’s storage by setting \(R' = 0.1 R\).

Original (100% storage)

25% of s.v.s (41% storage)

10% of s.v.s (16% storage)

5% of s.v.s (8% storage)

1% of s.v.s (2% storage)